Agroecology against the growth of megacities

Agroecology against the growth of megacities

To understand the relationship between agriculture and the birth of inhabited centres, it is necessary to start from the consideration that the human species is social and gregarious and has always been so: even hunters and gatherers, although mobile on the territory, acted and lived in groups and not by loners.

Farming is one of the oldest human activities, dating back thousands of years. It was one of the fundamental stages in the development of societies and human aggregations, allowing the transition from nomadic life to sedentary life. The history of agriculture can be divided into several key phases or periods, each characterized by significant innovations and developments.

– Neolithic Revolution (about 10,000-4,000 BC): This period marks an important turning point in the history of agriculture, as humans moved from hunting and gathering food to growing plants and raising animals. Agriculture developed independently in different parts of the world, such as the Near East, East Asia, North Africa and Central America.

– Ancient Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley (c. 4,000-1,500 BC): These regions were among the first to develop an organized form of agriculture on a large scale. Rivers such as the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia and the Indus (longest and most important river in present-day Pakistan) provided the water needed to irrigate the fields. Canalization and water management systems were developed to increase agricultural productivity.

– Ancient Egypt (about 3,200-30 BC): Agriculture in Egypt was closely linked to the Nile River. Every year, during the rainy season, the Nile overflowed, leaving deposits of fertile silt on the surrounding lands. The ancient Egyptians developed sophisticated irrigation systems to distribute water to their fields and used agricultural tools such as the plow and the ploughshare.

– European Agricultural Revolution (12th to 18th centuries): This period was characterized by a series of agricultural innovations in Europe. The introduction of crop rotation, in which fields were sequentially planted with different crops to avoid depletion of the land, and the adoption of new agricultural implements such as the spade and heavy plow, improved agricultural productivity.

– Green Revolution (since the mid-20th century): The Green Revolution represents a series of agricultural innovations that have helped increase global food production. The introduction of new high-yield crop varieties, the widespread use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and the adoption of intensive animal husbandry practices have helped increase agricultural yields, but have also raised concerns about sustainability and impact on the environment.

With the evolution of agricultural systems, demographic growth and the emergence of a more complex organization of work and society, the first cities developed. However, in the past millennia, the world has essentially been populated by farmers, hunters, fishermen, closely tied to the land, dispersed in small clusters throughout the territory. Urban societies had important roles, but small dimensions. During the Renaissance, in central-northern Italy, the most prosperous area in Europe, only ten inhabitants out of a hundred lived in urban centers with more than 10,000 inhabitants, against just three or four out of a hundred in France, Germany and England and one per hundred in the peripheral areas of the continent, to the north and east.

However, with the industrial revolution urbanization made a vigorous leap forward; industries and tertiary activities are concentrated in the cities; thus, for example, London reached a million inhabitants after 1800, and was then the most populous city in the world. Today there are more than 500 urban areas with over one million inhabitants, and the most populous urban complex in the world is Tokyo with almost 40 million inhabitants.

The urbanization process has rapidly accelerated; in 2013 urban populations exceeded rural ones, in 2018 they represent 55% of the total world population, almost double the amount in 1950.

The link between modern agriculture and the industrialization of systems is perfectly related to the expansion of the so-called megacities.

The evolution, often uncontrolled or uncontrollable, of the situations and movements of movement towards certain urban areas with the intensification of the population density and of productive and commercial settlements has produced, especially since the second half of the twentieth century, very extensive agglomerations which have been called megacities , a term used by J. Gottmann for the first time in 1961 to indicate this phenomenon.

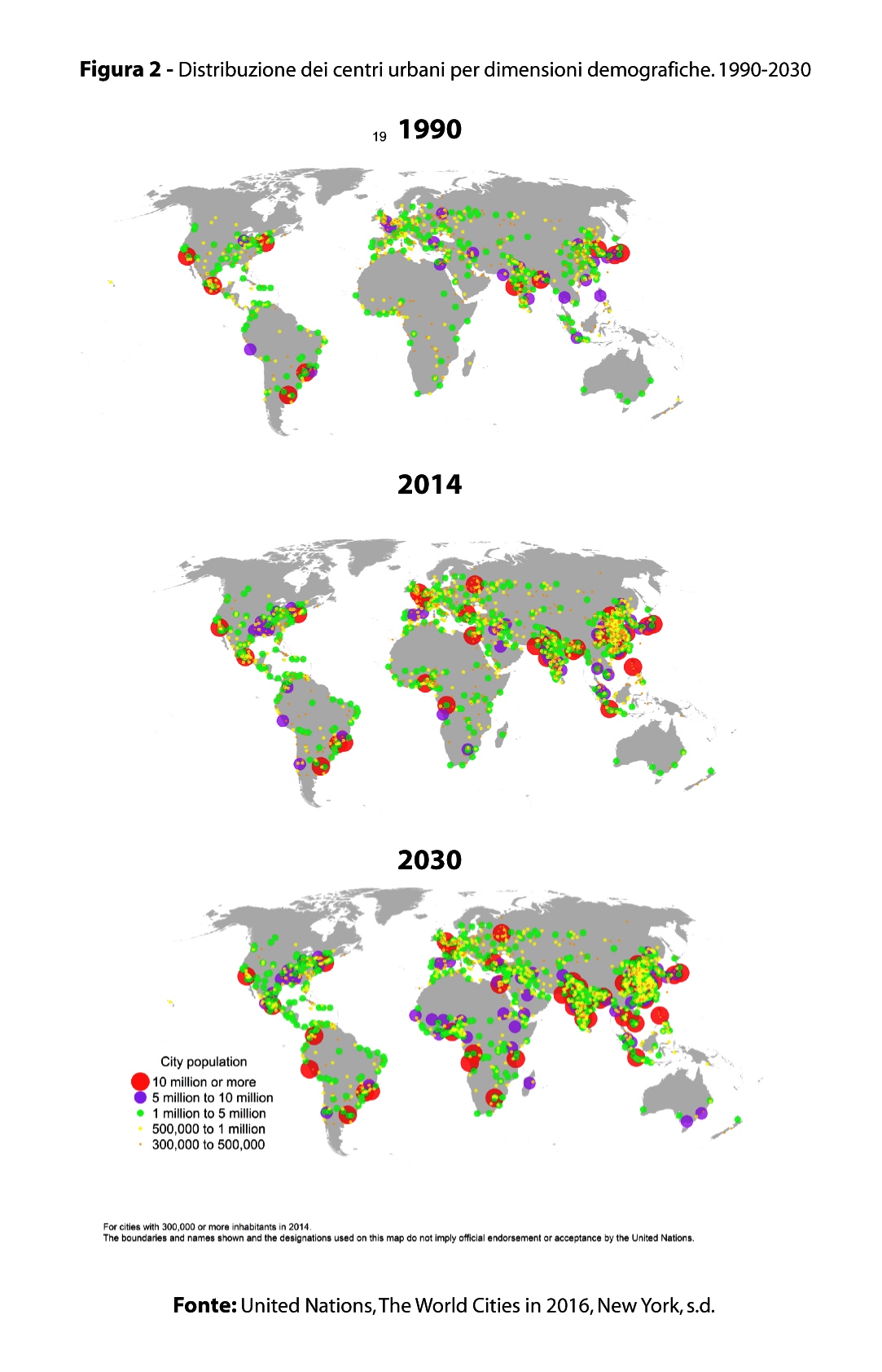

In 1950 there were only 2 megalopolises with over 10 million inhabitants (New York and Tokyo), today there are 31 and forecasts for the next few years are, to say the least, catastrophic, due to the consequences that all this can have on energy needs and on social imbalances.

In fact, urban growth will continue to occur – albeit at an increasingly slower speed – in the coming decades. According to United Nations estimates, by 2030 60% of the world’s population will live in urban areas, which will increase from 4 to 5 billion, while the rural population will remain almost unchanged at 3.4 billion. Cities with over half a million inhabitants from 1063 in 2016 will increase to 1393 in 2030, and their incidence on the world population will grow from 27.7% to 33.3%. The urban population therefore tends to concentrate in ever larger complexes: in 2016, about a fifth of the urban population lived in aggregates of more than 5 million inhabitants, and in 2030 almost a quarter.

The growth in number and size of large urban aggregates, particularly dynamic in Asia and Africa, obviously generates more than one cause for concern. Populations with above-average consumption live in these aggregates, more waste is produced and more greenhouse gases are emitted, soil is consumed twice as fast as population growth. In less developed countries, almost a third of the population lives in slums or informal settlements, with rudimentary services, precarious access to safe water sources, poor hygiene, subject to environmental risks, often without a permanent home and therefore at risk of expulsion.

In theory, urban areas should take advantage of the economies of scale generated by their size. The construction of roads, transport networks, water and energy distribution, if well planned, are in theory relatively less expensive, as is the provision of basic health and hygiene services.

However, it is known that the lack of adequate planning and efficient government and building speculation has prevented almost everywhere from enjoying these theoretical benefits of scale.

For this reason, the rapid development of the immense growth of large urban centres, foreseeable for the next decades, threatens the “sustainable development” that the international community is solemnly committed to pursuing.

In this direction, the advent of agroecological systems can determine a reversal of this trend since, according to its assumption, agroecology necessarily involves not only the reorganization of production systems but also a different connection between them and consumers.

Agroecology is in fact, within the broader scenario of the circular economy, that production and economic model where the connection between the various systems must be integrated and where the flows are not linear.

Agricultural biodiversification will also change the interface between producers and consumers, perfectly following the objectives of the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy. In this direction, the scenario of traditional markets, which developed and evolved with the advent of specialized agriculture, will change rapidly, requiring a closer relationship, also in terms of distance, between those who produce and those who consume, but also in terms of quality, having to devote more attention to individual needs.

Therefore, a system of market networks based on new approaches is envisaged among which emerge, among others, solidarity purchasing groups, better known by the acronym GAS, zero kilometer networks, and other experiences tending to bring link production and consumption.

These new experiences arise above all as a need to change a lifestyle in which the economic system, based on the capitalist market economy, does not guarantee the satisfaction of one’s needs on a level of parity, universality, equality of all citizens, generating at the same time all the aforementioned failures.

These are experiences that go beyond the sphere of the economy to become part of the field, as well as ethics, also of health and politics, the latter understood, not the one that had or should intervene to correct and regulate the market , which is not always the best rationaliser, since frictions are often triggered by the encounter between supply and demand which create waste and social damage; but a new way of doing politics which, through a strong reflection on critical consumption, a part of civil society claims to bring directly into the market.

The concept that underlies the GAS is that of the “short supply chain”, in other words the rapprochement between producer and final consumer, both in geographical terms, preferring the companies closest to the place where the group was formed, and in “functional” terms, cutting out intermediaries such as wholesalers and retailers, especially hypermarkets. In the case of GAS, the supply chain is as short as possible, in fact, consumers turn directly to the producers. The selection of products and producers by GAS members takes place through the criteria of the so-called “critical consumption”, since people choose products that meet certain requirements pursuing the objective of buying products that respect the environment and people.

These new systems are perfectly linked to the creation of circular cities and territories, strongly connected to issues such as sustainable development, resilience and climate change. There is currently no clear and shared definition of what constitutes a city or a circular territory. In scientific literature, the circular city is very often seen as a context capable of putting the principles of the circular economy into practice, attempting to close the cycles of the resources it uses, as well as achieving social engagement with its stakeholders (citizens, communities, businesses, administrators and knowledge stakeholders). The Ellen MacArthur Foundation states that a circular city incorporates circular economy principles into all of its functions, establishing an urban system that is regenerative by definition.

Regardless of the various definitions present, in general cities and territories are defined as circular to underline the innovative way of seeing, pondering and above all managing the economic and non-economic activities that take place in the city territory. In recent years, numerous cities have proposed strategies and embarked on paths towards circularity such as Rotterdam, Paris, London, Madrid and others.

In any case, the connection of systems and the change of lifestyles will necessarily lead to a recomposition of the urban fabric which, in some ways, the linear economy has led to a point of no return.

Suffice it to say that in Italy the periphery is increasingly depopulated (in the last 25 years one person out of seven has left), with nearly two million empty houses (one out of three is unoccupied) and increasingly elderly inhabitants (two per every young person). It is the photograph of small Italian municipalities that emerges from a recent study carried out by Cresme for Legambiente and Anci on municipalities with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants.

A small Italy but with a deep soul that goes from the Alps to the Apennines to get to the smaller islands; 5,627 small towns that cover 69.9% of the total number of municipalities in Italy (8,047). Of these, according to the study, almost half (2,430) are those who suffer from severe demographic and economic hardship, small villages that occupy 29.7% of the national land area, over 89 thousand sq km, a population density that does not reach 36 inhabitants per sq km; almost 13 times less than in municipalities with over 5,000 inhabitants.

In particular, in the last 25 years (from 1991 to 2015) in these areas there has been a decline in the working population (675,000 fewer inhabitants, i.e. -6.3% in municipalities with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants), one person out of seven has gone, an increase in the elderly (over 65s compared to young people up to 14 years of age have increased by 83%), with more than 2 elderly people for a young person. There are 1,991,557 empty houses against the 4,345,843 occupied ones: one out of every three is empty.

To remedy this social and, consequently, ecological and environmental disaster, it is necessary to reverse a political logic which has seen in the linear economy and in the centralization of powers and decisions a pathology with no possibility of any cure.

The only remedy for all this is to rethink a relationship between man and nature, to different links between social ecology and ecology, and in which agroecology is the only solution, within the circular economy , to cure what the United Nations defines as a Humanitarian Crisis.

Guido Bissanti