Apus apus

Apus apus

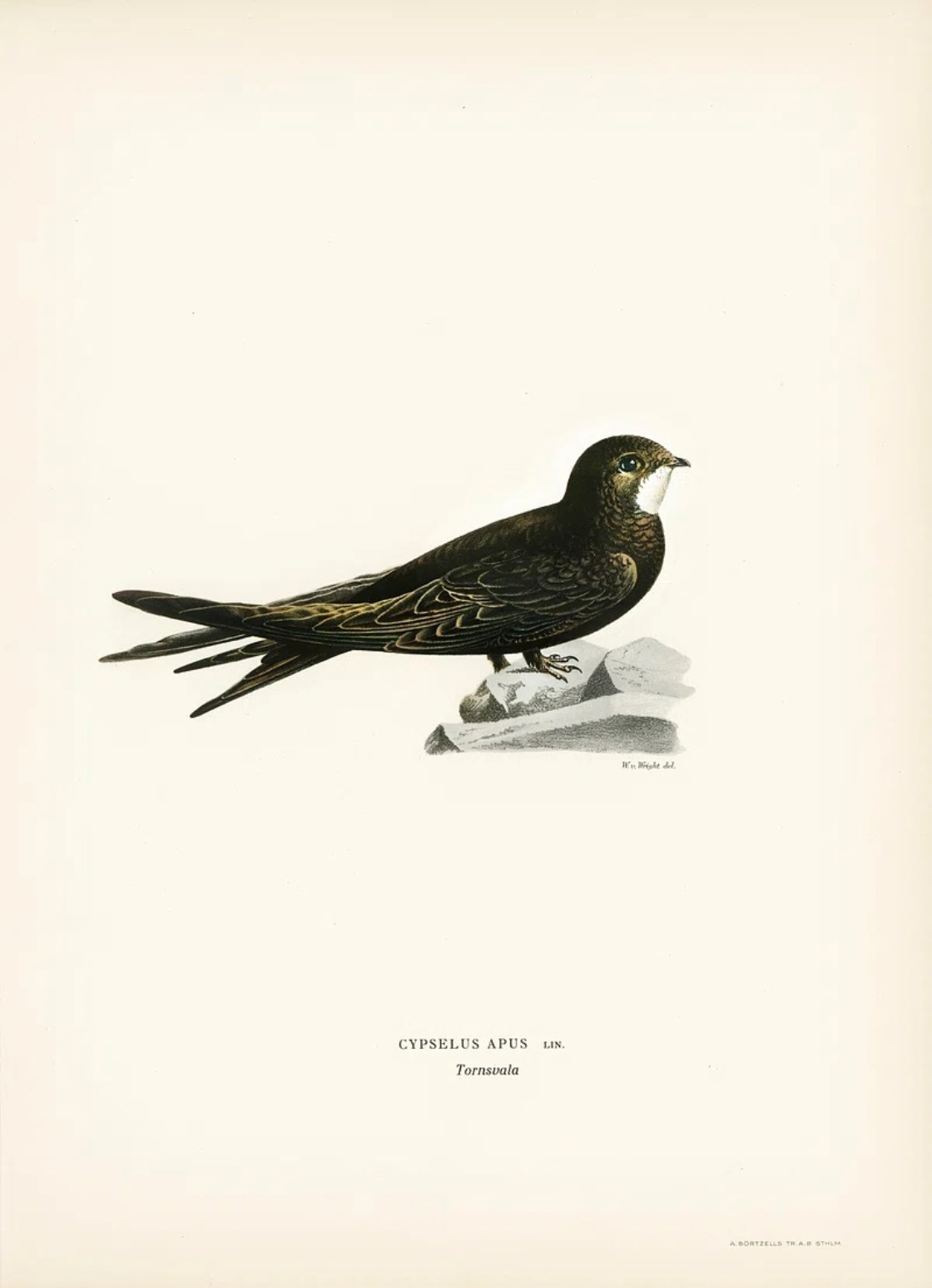

The common swift (Apus apus Linnaeus, 1758) is a bird belonging to the Apodidae family.

Systematic –

From a systematic point of view it belongs to:

Eukaryota domain,

Kingdom Animalia,

Phylum Chordata,

Aves class,

Subclass Neornithes,

Superorder Neognathae,

Order Apodiformes,

Family Apodidae,

Subfamily Apodinae,

Genus Apus,

Species A. apus.

The term is basionym:

– Hirundo apus Linnaeus, 1758.

The terms are synonymous:

– Cypselus apus (Linnaeus, 1758);

– Cypselus murarius Temminck.

The following subspecies are recognized within this species:

– Apus apus subsp. apus;

– Apus apus subsp. pekinensis (Swinhoe, 1870).

Geographic Distribution and Habitat –

The Apus apus is a migratory species between the African and European continents.

The breeding range extends from the northern Mediterranean to Scotland and Scandinavia. It also breeds in North-West Africa and the Middle East. It usually winters in sub-Saharan Africa, arriving in our latitudes around the end of April, and leaving again at the beginning of August.

In detail, their summer breeding range goes from Portugal and Ireland in the west to China and Siberia in the east. They breed as far south as North Africa (in Morocco and Algeria), with a presence in the Middle East in Israel, Lebanon and Syria, in the Near East through Turkey and throughout Europe as far north as Norway, Finland and much of of sub-Arctic Russia. They migrate to Africa following different routes, ending up in equatorial and sub-equatorial Africa, excluding the Cape. However, they do not breed in the Indian subcontinent.

Description –

The Apus apus is a small bird with very dark, almost black plumage that does not present sexual bimorphism, with minimal morphological differences between males and females. It has completely black plumage, except for the throat which is whitish.

It has a total length of 16-17 cm, a wingspan of 42-48 cm, for a weight of 31-56 grams.

The adult’s plumage is very dark brown, while the throat and chin are light. Juveniles have lighter throat plumage and upper body feathers are edged in white.

The wings are long and thin, carried backwards. The long sickle-shaped wings form a narrow crescent from whose concave center the short, forked tail protrudes.

The tail is slightly forked. The beak is very short, with a large mouth opening.

This bird species is often confused with swallows, to which however it is not even remotely related. The swallow, in fact, belongs to the order of passerines.

The flight, agile and powerful, is fast with sudden glides and turns, alternating with short flapping phases.

Characteristic are the continuously emitted screams which are: “shuirr – shuirr – shuirr”.

During group flights, especially frequent at sunset, it emits a strident and prolonged song, which, from May to mid-July, represents one of the most easily audible animal voices in population centers and European countryside.

Biology –

The Apus apus is a bird that often forms stable pairs until one of the two partners dies, but the true bond of fidelity is the one with the cavity chosen to reproduce, where the partners punctually find each other after having migrated and wintered separately.

The nest is built with material collected in the air inside artificial cavities on buildings and human constructions (ledges, roof tiles, post holes, shutter boxes), rarely on trees and cliffs. They build nests by mixing feathers and plant material with saliva.

The female lays 1 to 3 white eggs, sometimes 4, in late spring and incubates them together with her partner for 18-21 days.

Then the nestlings are raised for about forty days by both parents until they are able to fly and get food on their own.

Ecological Role –

The scientific name Apus, meaning footless, has fostered the belief that such birds have atrophied feet, which would prevent them from resuming flight once they hit the ground. In reality, the foot of swifts is far from atrophied, and is an example of effective evolutionary adaptation: it represents a robust pincer, in which all four toes consist only of the proximal phalanx and the claw, without intermediate phalanges. This anatomical conformation allows the bird to cling firmly to vertical walls and protrusions and also constitutes an important attack and defense tool.

This bird hunts insects in flight without slowing down the speed of its flight. A social species, it loves to live in flocks, sometimes very numerous.

The swift spends much of its time in the air where it feeds, mates and even sleeps. It flaps its wings quickly and is very skilled in dives, climbs and turns. It is extremely fast and can reach speeds of 160 to 220 km/h in flight, a true record for birds of its size.

It feeds exclusively on aeroplankton, that is, aerial insects and non-flying invertebrates dispersed by the wind at great heights, several of which are harmful to agriculture and humans, such as nematocera which include, among others, the tiger mosquito.

This bird has the characteristic of being able to sleep in flight. This ability was confirmed in 2016 by a study conducted by biologists from Lund University (Sweden) and published in the scientific journal Current Biology, based on the use of micro data loggers to track a group of specimens during migration to and from areas wintering in sub-Saharan Africa.

Thanks to the evolution of technology it was finally possible to confirm the observations of Lazzaro Spallanzani in 1797, Emil Weitnauer in 1951 and, in more recent times, of the ornithologist Luit Buurma, known for the use of radar to follow the nocturnal activity of swifts and for studies on the bird strike phenomenon (collision between aircraft and birds).

However, the way in which the state of rest occurs in the common swift while it flies is still under study.

This bird is a long-range migrant: it nests in almost all of Europe, from the Iberian peninsula to Scandinavia, in the countries of the Mediterranean Sea, from North Africa to the Middle East, and in part of Asia, up to China and Siberia; winters in much of sub-Saharan Africa. It lives in cities and towns, especially with historic centers full of cavities, sometimes even on rocky coasts or other natural cliffs, while commonly in the taiga and now only locally elsewhere it nests in cavities dug by woodpeckers in trees.

As regards the conservation status, if at a global level the conservation status of the common swift is classified as minimal risk (LC), with a global population estimated at around one hundred million individuals; in Europe it was considered close to threatened (NT) in 2021. The causes are identified in the loss of nesting sites, consisting mostly of ancient and modern human constructions, following the renovation, renovation or demolition of buildings. The negative trend is also recorded in Italy in some local areas such as Lombardy.

Subjects of a geolocated tracking study showed that swifts that breed in Sweden winter in the Congo region of Africa. Swifts spend three to three and a half months in Africa and a similar amount of time breeding; the rest they spend in flight, flying home or away. Unsuccessful breeders, chicks and sexually immature yearlings are the first to leave their breeding area. This is followed by breeding males and finally breeding females. Breeding females stay longer in the nest to rebuild their fat reserves. The departure time is often determined by the light cycle and begins on the first day with less than 17 hours of light. For this reason, birds further north, for example in Finland, leave later in the second half of August. These latecomers are forced to endure rapidly shortening days in Central Europe and are barely seen by bird watchers.

The prevailing direction of travel across central Europe is south-southwest, so the Alps do not represent a barrier. In bad weather, swifts follow the rivers, because there they can find a better food supply. The population of Western and Central Europe crosses the Iberian Peninsula and Northwest Africa. Swifts from Russia and south-eastern Europe have made a long journey to the eastern part of the Mediterranean. It is unclear where the two groups meet. The western group of swifts mostly follows the Atlantic coast of Africa, otherwise they would have to cross the Sahara. Once they arrive in the humid savannah, they turn south-east to reach the winter feeding areas. During the summer in Africa there is a great abundance of insects for swifts, as the region is located in the intertropical convergence zone. Swifts have an almost continuous presence in the sky.

Some swifts, usually a few sexually immature one-year-olds, remain in Africa. Most fly north across Africa, then turn east toward their destination. Birds use low-pressure fronts during their spring migrations to take advantage of the southwestern flow of warm air, and on the return journey, they ride northeasterly winds on the backs of low-pressure fronts.

In Central Europe, swifts return in the second half of April and the first half of May and prefer to stay on lowlands and near water rather than in high places. In the more northern regions the swifts arrive later. The travel time has a huge influence on the arrival date, so swifts can return to a region at different times from year to year.

Guido Bissanti

Sources

– Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

– GBIF, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

– C.Battisti, D. Taffon, F. Giucca, 2008. Atlas of nesting birds, Gangemi Editore, Rome.

– L. Svensson, K.Mullarney, D. Zetterstrom, 1999. Guide to the Birds of Europe, North Africa and the Near East, Harper Collins Publisher, United Kingdom.

Photo source:

– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_swift#/media/File:Apus_apus_-Barcelona,_Spain-8_(1).jpg