Reproduction of the Giant Sequoia

Reproduction of the Giant Sequoia

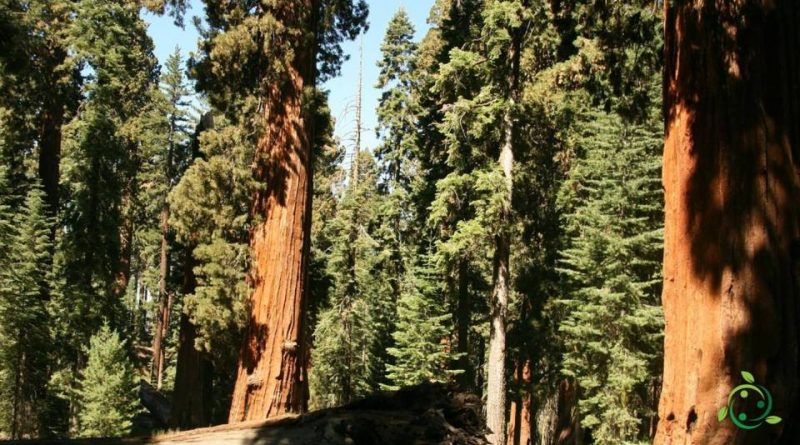

The giant sequoia or wellingtonia (Sequoiadendron giganteum, Lindley, Buchholz, 1939), is a tree of the Cupressaceae family native to the Sierra Nevada in California.

Suitable breeding habitat –

Sequoiadendron giganteum is a plant whose natural distribution is limited to an area of the western Sierra Nevada, in California.

It is a paleo endemic species that grows in scattered woods, with a total of 81 natural formations that encompassing a total area of only 144.16 km2.

This species grows in nowhere pure stands, although in some small areas the stands approach a pure condition.

The northern two-thirds of its range, from the American River in Placer County south to the Kings River, has only eight disjoint woodlands. The remaining southern woodlands are concentrated between the Kings River and Deer Creek Grove in southern Tulare County. The size of these small woods varies from 12.4 km2, with 20,000 mature trees, to small woods with only six living trees. Many are protected in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks and Giant Sequoia National Monument.

Its habitat is characterized by a humid climate characterized by dry summers and snowy winters. Most of the giant sequoia groves are found on residual and alluvial soils with a granite base. The elevation of redwood forests generally ranges from 1,400–2,000m in the north to 1,700–2,150m in the south.

Giant sequoias are generally found on the south-facing sides of the northern mountains and on the northern walls of more southern slopes.

Unfortunately, most giant sequoia groves are currently undergoing a gradual decline in density.

Propagation –

The giant sequoia is a very popular ornamental tree in many areas. It is successfully cultivated in most of western and southern Europe (where it has been introduced to Europe and Italy, where specimens over 40 meters in height are also found).

It has been implanted in the northwestern Pacific of North America from north to southwestern British Columbia, the southern United States, southeastern Australia, New Zealand, and south-central Chile. It is also grown, albeit with less success, in parts of eastern North America.

Sequoiadendron giganteum can withstand temperatures of -31 ° C or colder for short periods of time, provided the soil around the roots is insulated with heavy snow or mulch. Outside its natural zone, foliage can suffer from harmful wind burns.

Many varieties of this plant have been selected, especially in Europe, including blue, compact blue, powder blue, hazel, pendulum or weeping varieties and grafted cultivars.

The propagation of this plant can be carried out by seed, with sowing in containers in a cold seedbed in spring.

This plant is a pioneer species that has difficulty reproducing in their original habitat (and very rarely reproducing in cultivation) as the seeds can only successfully grow in full sun and in mineral-rich soils, free from competing vegetation.

It can also be propagated for wood cuttings in the summer or semi-mature cuttings in late summer.

Ecology –

Giant sequoias are in many ways adapted to forest fires. Their bark is unusually fire resistant, and their cones normally open immediately after a fire.

This plant is a species that successfully reproduces only in full sun and in soils rich in minerals, free from competing vegetation. Although the seeds can germinate in the spring, in the moist humus that forms after the rotting of the needles, these seedlings will die as the soil then dries up in the summer. They therefore require periodic fires to clean up competing vegetation and the presence of humus in the soil before effective regeneration can take place. Without fire, shade-loving species will suffocate young sequoia seedlings and sequoia seeds will not sprout.

When these plants are fully grown, they typically require large amounts of water and are therefore often concentrated near streams. Squirrels, finches and sparrows also consume newly sprouted seedlings, preventing their growth.

Fires bring hot air upward by convection, which in turn dries and opens the cones. The subsequent release of large quantities of seeds coincides with the optimal conditions of the seedbed after the fire. Loose ground ash can also act as a cover to protect fallen seeds from ultraviolet radiation damage. Due to fire suppression efforts and cattle grazing during the early and mid-20th century, low intensity fires no longer occurred naturally in many woodlands and still do not occur in some woodlands today.

Fire suppression leads to the buildup of organic matter in the soil and dense growth of fire-sensitive silver fir, which increases the risk of more intense fires affecting firs which then threaten the foliage of mature giant sequoias. In 1970, the National Park Service began burning its woods to correct these problems. Current policies also allow natural fires to burn.

In addition to fire, two animal agents also aid in the release of giant sequoia seeds. The more significant of the two is a longhorn beetle (Phymatodes nitidus) that lays eggs on cones, in which the larvae then dug holes. The reduction of the vascular water supply to the cone scales allows the cones to dry out and open due to the fall of the seeds. Cones damaged by beetles during the summer will slowly open over the next few months. The other agent is the Douglas squirrel (Tamiasciurus douglasi) which gnaws the green, fleshy scales of the younger cones. Squirrels are active all year round, and some seeds are peeled off and dropped as the cone is eaten.