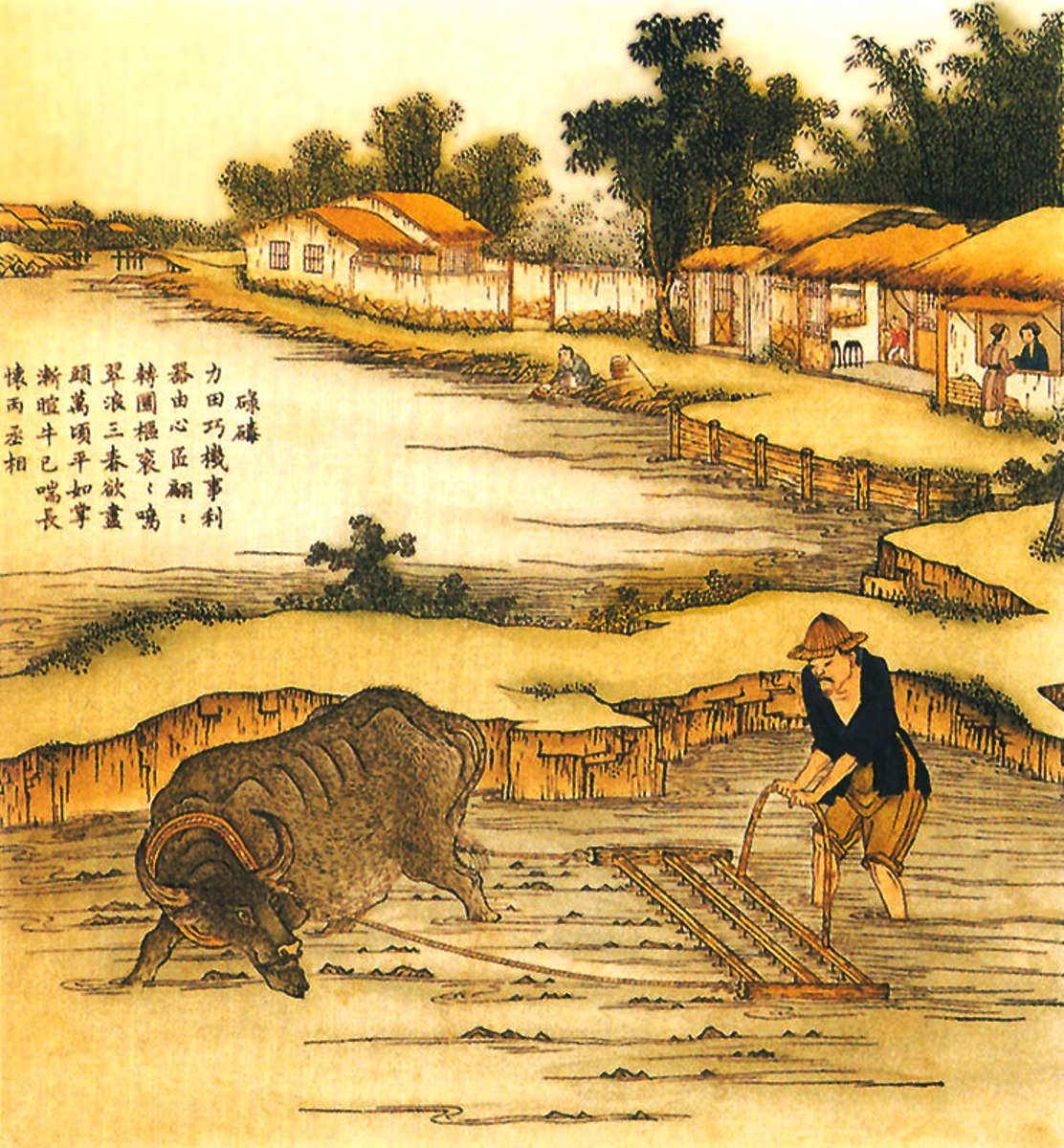

Agriculture in ancient China – part VI

Agriculture in ancient China – part VI

The traces on the previous tracks are quite frequent; for example the following passage is reported from the Spring and Autumn of Mr. Lü, which contains a citation from a text entitled Book of the Prince Miglio (Houji shu, in reference to the progenitor of the Zhou dynasty):

– “Do you know how to make low and marshy ground fertile? Do you know how to protect dry soils and temper them with moisture? […] Do you know how to make the panicles of your millet well rounded and the skins thin, that its grains are numerous and full, so as to have food in abundance? How can you achieve this? Applying these fundamental principles of soil processing: it is necessary to weaken the strong [soils] and strengthen the weak ones. The rested [soil] must work, the tired one must rest. The lean must be fattened, the fat lost. The compact must be made soft, the soft compact. The wet must be dried and the dry wet […]. He works the soil five times and weeds it five times. Strictly observe these rules. (Lüshi chunqiu, p. 27 et seq.) “.

This passage is in turn quoted in the Essential techniques for the people, followed immediately by a quote from the Book of Fan Shengzhi: “When apricot trees begin to bloom, they immediately plow the light and weak soils; repeat the operation when the apricot flowers fall to the ground. After plowing, immediately flatten the soil […]. If the soil is very light, it is advisable to have it trampled by the cattle. This is what is called “strengthening weak lands” (Qimin yaoshu jinshi, 1.12, p. 1).

However, the Book of Prince Miglio is not mentioned in the Han bibliography and it is probable that it was not directly accessible to Jia, and perhaps not even to Fan; however, it was mentioned in the Spring and Autumn of Mr. Lü, a very popular and well-known text of philosophy of Nature.

From this we can deduce that Jia did not directly know all the works mentioned in his book, but in ceri cases he quoted passages from others, drawing from the sources accessible to him entire passages that included a quotation from a previous work and a composed historical sequence from exegesis, commentary and favorable or contrary evidence provided by subsequent authors.

Even if these passages were followed by the author’s observations, according to a customary model of the Chinese culture of those times, however, it appears surprising that an obscure official at the beginning of the 6th century could have access to the consultation or even have a copy (made by himself or by someone else) of such a large number of texts that, of course, at that time only circulated in manuscript form.

Apart from these considerations, the question has long been debated as to whether the essential techniques for the people should be addressed to a public made up of simple farmers, as the title seems to suggest, or rather constitute a manual for the large landowners (Kumashiro 1971; Herzer 1972 ).

In a nutshell, did Jia Sixie write as an official or as an owner?

A historian of western agronomy will perhaps find it futile or surprising that this point can be discussed; in the Greek, Roman and European agronomic tradition the experience of the great agricultural estates has represented, in fact, a constant source of experiences and innovations.

In the West, in fact, writers such as Cato (234-149 BC), Columella (I century AD) or Gervase Markham, while being convinced of being repositories of universally valid knowledge that would have contributed to the general well-being, turned to their peers, and not to the simple peasants.

In the West in practice, it has never existed, and in some ways there is still no equivalent of this form of agricultural disclosure, written by officials for the wider public, which in China played a very important role instead.

The idea that the state could promote the improvement of the quality of farmers’ work, or that this was the most appropriate means to promote progress in agriculture, was completely foreign to the Western mentality.

In fact, to date, this planning flaw is still inherent in the modern Western states, which look more to the agricultural market (from the Treaty of Rome in 1960 to the present) than to a sustainable planning of production and resources.

In China, on the other hand, this view, over 2,000 years ago, was already one of the cornerstones of a true agricultural planning, even if we cannot say with certainty that some of the oldest treatises were specifically aimed at a peasant public , as is the case of some large and influential works composed in later periods.

At that time almost all Chinese governments implemented policies to encourage and improve the work of smallholders; a strategy that was in line with the Confucian political ethic, which required governing for the benefit of the people, and to the law-making principle of increasing state revenues through the direct taxation of agricultural producers; moreover, the presence of large landed estates and the related landowners could also represent a threat to the central government.

The logic was obviously that the control of large portions of territory by the richest families not only came at the expense of small farmers, forced to pay heavy rent or to accept the humiliating condition of servants, but also erected a barrier between government and the people, and caused a decrease in tax revenues. A policy that, however, seen from the side of the peasants, when there was scarcity of arable land, it became very difficult and risky to make a living as a direct cultivator and, in a situation of social instability, the fact of being employed by a powerful local owner had undoubted advantages.

It was for this reason that during the entire Han Han dynasty the state enacted a series of effective laws against the large landed estate and for the assignment of plots of land to the peasants. At this time new irrigation systems were built and the farmers were instructed on the different cultivation techniques, with a considerable improvement in productivity.

Guido Bissanti