Capra ibex

Capra ibex

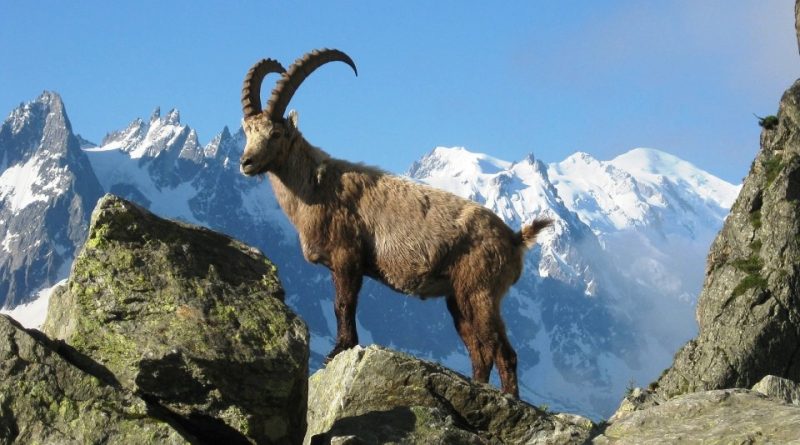

The Alpine ibex (Capra ibex L. 1758) is a mammal belonging to the Bovidae family.

Systematics –

From the systematic point of view it belongs to the Eukaryota Domain, Animalia Kingdom, Phylum Chordata, Mammalia Class, Artiodactyla Order, Bovidae Family, Caprinae Subfamily and therefore to the Capra Genus and to the C. ibex Species.

Geographic Distribution and Habitat –

The Alpine ibex is a mammal widespread throughout the Alps, from the Maritime Alps in the west to the Alps of Carinthia and Slovenia in the east, at altitudes between 500 and 3,000 m; it is also present in the Caucasus, Central Siberia, Mongolia, Afghanistan, Palestine, Arabia, Egypt and Sudan.

Nearly extinct, its range has expanded considerably during the twentieth century, although its distribution is still quite fragmentary. In fact, with the exception of the population present in the Gran Paradiso National Park, all the current ones are the result of reintroductions (France, Switzerland, Austria and Germany) or new ones (Slovenia and Bulgaria).

The typical habitat of this Bovide is that of high altitude rocky environments, above the tree line. The steep rocky ridges facing south rich in herbaceous vegetation are a preferred environment. In subalpine areas it is found in open and sunny areas with the presence of rocky outcrops.

Description –

The Alpine ibex, from a morphological point of view, is somewhat similar to a domestic goat, with an evident sexual dimorphism.

This mammal has a variable head-body length between 105 and 150 cm, with a height at the withers of 65-90 cm, tail of 12-15 cm; the weight of the males varies between 75 and 120 kg, that of the females between 40 and 55 kg.

The horns are well developed in males, less so in females. Beyond the size, the sex is distinguishable only by the reliefs on the front of the horns.

In the summer the coat takes on a reddish-gray hue with darker areas scattered on the body, such as on the cheeks, chest, shoulders, back, throat and apex of the tail. In winter the whole coat takes on a general color that tends more to brown-brown.

Biology –

The mating and mating period of these mammals occurs in the month of December – January and is preceded by fights between the males who have herded with the females; the clashes between males, however very spectacular, are limited and sanction the supremacy of single individuals.

At this time, the dominant adult males actively search for females in heat, showing characteristic attitudes of submission: typical are the horns upturned on the back, neck tense, tail raised like a plume to reveal the white anal mirror.

Gestation lasts between 160 and 180 days, at the end of which only one baby is born, rarely two. The babies are nursed for 6 months and stand up after a few minutes and are immediately able to follow the mother on the sheer walls.

Ecological Role –

The Alpine ibex is an animal that lives beyond the limit of the arboreal vegetation, between steep rocky walls and in the alpine meadows and, since to face the winter, the ibex never goes down into the forest, it needs exposure to the south at high altitude .

Furthermore, the ibex is essentially a diurnal animal and is active even before sunrise. From the early hours of the day until dusk, he spends his days on the grassy terraces well exposed to the sun.

It is a gregarious species that lives in herds made up of females, pups and sub-adults of both sexes. The groups of males include subjects over 4-5 years of age and can reach 100 units in spring. The older subjects tend to have a solitary life or are aggregated in small groups of 4-6 elements, including also young animals. Finally, there are herds of females with young and young up to two years. During the summer you can also observe the so-called nurseries, that is groups of kids, up to 15-20, which are controlled by one or two females while the other mothers are looking for food.

The diet of these mammals consists essentially of grasses from pastures, sprouts of shrubs and in winter also of Mosses and Lichens.

An adult specimen can eat up to 15 kg of grass per day, including juniper, rhododendron, moss and lichen buds. It is not uncommon to meet in the mountains, on the sides of the roads, small blocks of salt destined for groups of ibex because, like other species of the genus Capra, it is greedy for salt as its body accuses an effective need for sodium, usually little available in forages. This mammal drinks little, often contenting itself with morning dew.

The spring diet is linked to the change of vegetation and this species feeds on shrubs of which it especially appreciates the shoots, and which it grazes by standing upright on its hind legs. In winter, on the other hand, dry herbs are the basis of the diet but shrubs also appear, such as green alder, lichens and more rarely conifer needles.

The history of the Capra ibex is long and characterized by a difficult relationship with man. In fact, about 100,000 years ago, the ibex lived in all the rocky regions of central Europe; inspiring the Paleolithic peoples who drew it in the caves in which they lived, as it appears in the mural paintings of the Lascaux cave in France.

This long period sees it present throughout the Alps up to the fifteenth century; unfortunately, the development of firearms soon marked its end in those territories. To this must be added the medicine of the time largely centered on superstition.

The horns were ground to dust as a remedy for impotence and his blood as a remedy for kidney stones. The stomach was used to fight depression. These beliefs persisted until the nineteenth century, when there were now only a few hundred individuals in the Italian and French Alps, while it had completely disappeared in Switzerland.

Game for the consumption of its meat contributed in part to the disappearance of the ibex. In fact, its meat has always been consumed since ancient times.

Then the species was protected for the risk of extinction and, after sufficient repopulation, hunting permits were resumed in some countries such as Switzerland, where the largest population lives. Ibex hunting is prohibited in Italy, but you can import its meat, which usually arrives frozen from abroad.

Ibex meat, as well as for direct consumption, is traditionally used for the preparation of certain cured meats such as mocetta in Piedmont and Valle d’Aosta.

The survival of this mammal is due to King Vittorio Emanuele II who had the last specimens protected in 1856, to reserve them for his personal hunting in a private reserve located in Valsavarenche where, by his order, a group of gamekeepers protected them from other hunters. To date, the Valle d’Aosta with Piedmont are the only regions of the Alpine arc where the species has never disappeared in historical times.

The species was thus saved thanks to the establishment, in 1856, of the Gran Paradiso Royal Hunting Reserve and subsequently, in 1922, of the Gran Paradiso National Park. Subsequently, the reintroduction operations, launched with a pioneering spirit by the Swiss Confederation at the end of the 19th century, led to its reappearance in 175 different European Alpine areas.

Today, despite the relative fragmentation of its range, the population of this mammal is currently growing significantly.

Furthermore, based on census data, the IUCN Red List classifies Capra ibex as a low-risk species (Least Concern).

As far as the protection measures are concerned, the species is included in Appendix III of the Bern Convention and is subjected to measures regulated by different national legislations which provide in some cases the absolute ban on hunting (France, Germany and Italy), in others the authorization for selective culling (Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia and Bulgaria).

In the 1990s, a total population of about 30,000 was estimated. Of these, about 15,000 live in Switzerland, 10,000 in France, 9,700 in Italy, 3,200 in Austria, 250 in Slovenia and 220 in Germany.

Guido Bissanti

Sources

– Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

– Gordon Corbet, Denys Ovenden, 2012. Guide to the mammals of Europe. Franco Muzzio Publisher.

– John Woodward, Kim Dennis-Bryan, 2018. The great encyclopedia of animals. Gribaudo Editore.