Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Guadalupe Mountains National Park

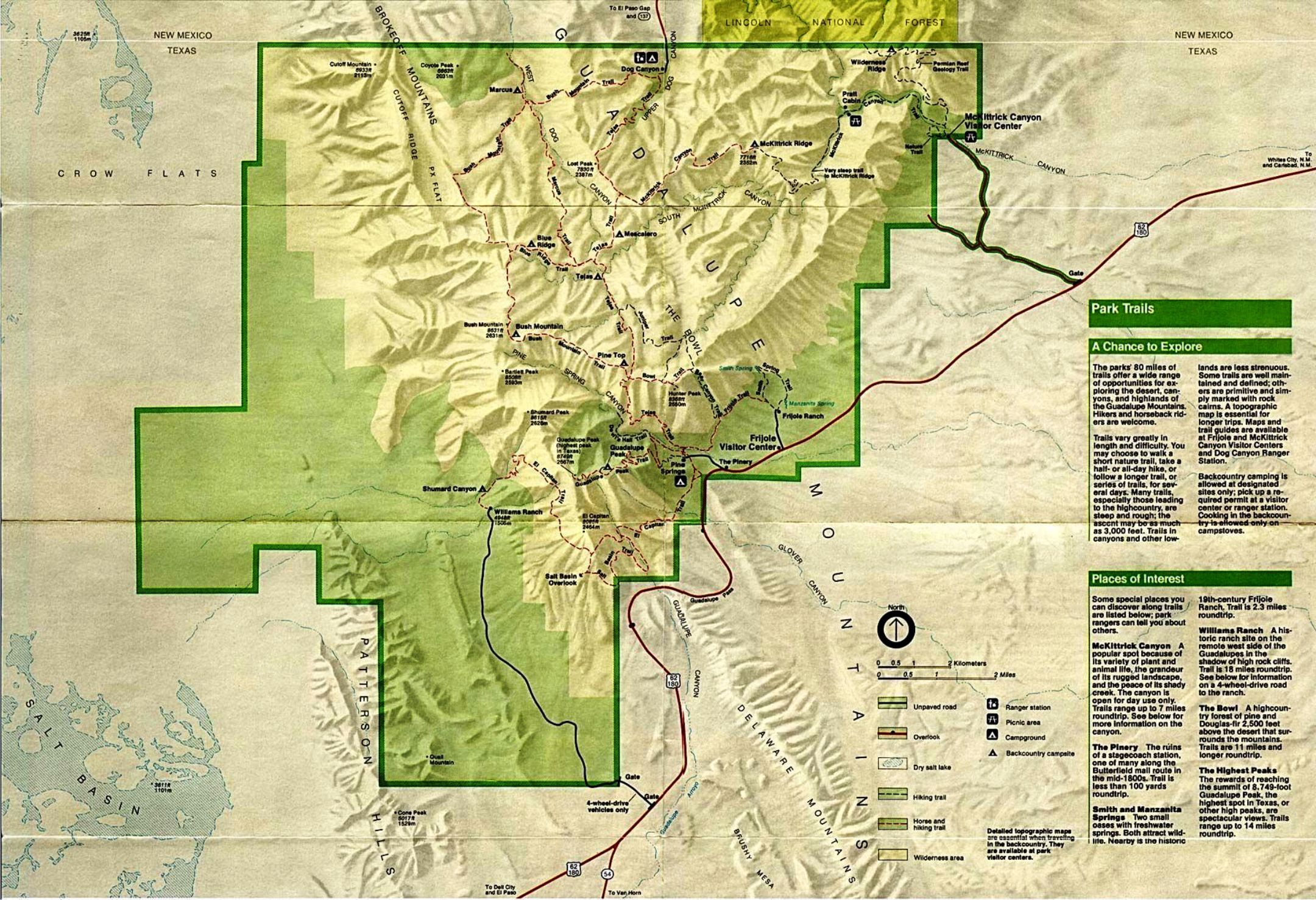

Guadalupe Mountains National Park, whose WDPA Code is: 2984 is a United States National Park located in Texas.

This park has a land area of 349.71 km² and is managed, like all national parks in the United States, by the National Park Service.

Guadalupe Mountains National Park is located in West Texas and was established on September 30, 1972 to preserve the Guadalupe Mountains region.

Geology –

The area that characterizes the Guadalupe Mountains National Park dates back to the geological period of the Permian; a period that occurred from 251 to 299 million years ago.

At that time the earth had already seen life diversify from simple and primitive forms such as algae and fungi to amphibians, fish and insects. The earth’s surface had also evolved and shifted. Thin plates of crust constantly moved on the softer material below, constantly changing the position of the continents. Through much of the early and middle Permian all continents were united, forming the supercontinent of Pangea. Much of present-day New Mexico and Texas occupied the western edge of this huge landmass near the equator. A vast ocean surrounded Pangea, but a narrow inlet, the Hovey Channel, connected the ocean with the Permian Basin, an inland sea that covered parts of what is now northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. The Permian basin had three arms: the Marfa, Delaware and Midland basins. The central arm (the Delaware Basin) contained the Delaware Sea which covered an area 150 miles long and 75 miles wide over what is now West Texas and Southeastern New Mexico.

During the central part of the Permian, a coral reef developed along the edge of the Delaware Sea. This used to be Capitan Reef, now recognized as one of the best preserved fossil reefs in the world. For several million years, Captain Reef expanded and thrived along the edge of the Delaware Basin until events altered the critical environment for its growth some 260 million years ago. The outlet connecting the Permian Basin to the ocean narrowed and the Delaware Sea began to evaporate faster than it could be replenished. The minerals began to precipitate from the evanescent waters and drifted to the bottom of the sea, forming thin alternating bands of mineral salts and mud. Gradually, over the course of hundreds of thousands of years, these thin bands completely filled the basin and covered the reef.

About 80 million years ago, tectonic compression along the western edge of North America caused the slow uplift of the region that included western Texas and southern New Mexico. A transition in tectonic events 20-30 million years ago initiated the formation of steep faults along the western side of the Delaware basin. Movement on these faults over the past 20 million years has caused a long-buried part of Captain Reef to rise several thousand feet above its original position. This raised block was then exposed to wind and rain causing the overlying softer sediments to erode, uncovering the hardest fossil reef and forming the modern Guadalupe Mountains. Today the reef towers above the desert floor as it once loomed over the Delaware sea floor 260 to 265 million years ago.

Within this area there is Guadalupe Peak, the highest peak in the State of Texas (2,667 meters above sea level), overlooking the Chihuahua desert, and the El Capitan peak.

Flora –

The biological diversity within the Guadalupe Mountains National Park is exceptional and includes more than 1000 plant species. While many of these are common desert species like ocotillo and prickly pear, others are found only in the park and nowhere else in the world.

In part, the extraordinary diversity can be attributed to significant geographical variations in an extremely rugged landscape. Steep-walled canyons, high country ridges, vast expanses of desert plains and lush riparian oases offer the opportunity for unique and contrasting living zones that span thousands of acres with over 5000 ‘of elevation gain.

The plants that grow here have survived not only the components that make up the landscape, but also the extremes of temperature, aridity and relentlessly powerful winds, all common factors of the park’s desert climate. Plants have evolved elegant methods for tolerating or avoiding desert conditions. Some, like cacti, have thick fleshy stems that store water and thorns that not only act as fierce armor against predators, but also help reflect the sun’s radiant heat. Many species avoid desert extremes by clinging tightly to limited but reliable seepage and shady springs. The annual wildflowers that grow here avoid drought altogether with a compressed and complete life cycle – from bud to seed – that occurs only in conjunction with the summer monsoon rains.

Fauna –

The Guadalupe Mountains rise abruptly from the surrounding desert to form an island of extraordinary diversity. Within the park there are several ecosystems. These include the tough Chihuahua desert community, lush oak and maple woodlands along the waterways, rocky canyons, and mountain forests of ponderosa pines and Douglas firs. Together, these ecosystems provide habitat for 60 mammal species, 289 bird species, and 55 reptile species.

At first glance, the desert may seem barren and almost lifeless. A closer look, however, will reveal that it does indeed support an amazing diversity of wildlife. Desert animals are often difficult to see as many of them are nocturnal. Many desert animals adapt to the hot, dry environment by going out after dark, when temperatures are much cooler and conditions aren’t as dry. Nocturnal desert animals include fox, coyote, mountain lion, bobcat, badger, Texas banded gecko, and around 16 bat species. Mule deer, javelinas, and black-tailed hares are seen early in the morning or late in the evening when temperatures are cooler.

Desert reptiles include the western diamondback rattlesnake, bullsnake, coachwhip snake, prairie lizard, collared lizard, spiny slit lizard, and Chihuahua spotted whiptail. Almost all of the lizards found in the park can be seen during the day. Scorpions and desert millipedes are nocturnal hunters who seek out insects, spiders, and small lizards at night. In the fall, tarantulas can often be seen looking for mates. The rest of the year, tarantulas rarely leave the shelter of their burrows.

One of the most unique and unexpected ecosystems of the Guadalupe Mountains is the riparian or riverside forest. Riparian forests are found in places where there is water. The mule deer is one of the most common animals seen in riparian areas. Nocturnal mammals such as skunks and raccoons can also be found here. Long-eared sunfish can be seen in some of the park’s headwaters, as well as in McKittrick Canyon. The creek that runs through McKittrick Canyon is also home to a small population of rainbow trout. Although amphibians are rare in the desert, the Rio Grande leopard frog can occasionally be encountered near spring-fed pools in McKittrick Canyon or in Manzanita and Smith Springs.

Rocky canyons are home to ring tails, rock squirrels, and a variety of reptiles including rock and black-tailed rattlesnakes, mountain patchnose snakes, and tree lizards.

On the mountain peaks, more than 900 meters above the desert, extensive pine forests can be found. It is usually at least ten degrees cooler on mountain tops than at lower elevations. The montane forests are home to animals such as moose, black bears, gray foxes, striped and pig-nosed skunks, porcupines, mule deer, mountain lions, and short-horned lizards.

Guido Bissanti