Agriculture in ancient China – part II

Agriculture in ancient China – part II

The biggest problem with farming in the period under review was that the share of arable land assigned to each farmer was insufficient. From recent archaeological finds it has been possible to verify that the average plot of a typical peasant family tenant, with five people able to work the land, was not larger than 20 ÷ 30 mu (corresponding to 9173 ÷ 13.760 m2 approx.). An ideal family of farmers with five members, in order to lead a normal life, would have had to own about 100 mu (45.865 m2), and at that time not even the richest of the estates reached this extension.

Farmers thus had to try to increase productivity and, at the same time, obtain additional external income. In order to increase productivity it was necessary to increase the workforce, while to procure external income other activities had to be started. Han farmers adopted both strategies and eventually managed to develop sophisticated farming techniques and a type of economic organization of agricultural properties that were preserved even in later centuries.

The cultivation systems had however already undergone an evolution in the period of the Spring and Autumn and in that of the fighting States.

During the 5th century B.C. a group of agronomists (nongjia) had preached the value of agriculture and had advocated knowledge of agricultural sciences.

In the ancient bibliographies of the history of the Han dynasty some titles of their presumed works are mentioned, not received by us. The ancient methods of cultivation are however described in specific chapters of the literature before the Qin: the Book of the Master Guan (Guanzi), perhaps compiled between the V and the III sec. BC, included chapters on soil conditions; the work of Lü Buwei (Springs and Autumns of Mr. Lü, Lüshi chunqiu), 3rd century a.C., contained specifics on the management of the fields, on how to improve the quality of the land and on the effects of a correct choice in cultivation times.

In addition, there were some old almanacs of agricultural activities in the form of a calendar, such as the Little Xia calendar (Xia xiaozheng) and the monthly Ordinances (Yueling), chapters of the Confucian anthology Memoirs on rites (Liji), both compiled in the late 3rd century. B.C.

In these treaties, practical knowledge accumulated in the period prior to the unification of Qin and Han had been accumulated in the form of a written tradition.

The principles contained in these works believed that, in order to increase yields, environmental conditions should be exploited to the full – ie the climate, atmospheric conditions (such as humidity), the quality of the soil, water supply, as well as considerably increase the use of labor.

However, the accumulated knowledge was based on the need for farmers to pay the utmost attention to the choice and rotation of crops, the selection of seeds, the use of various types of fertilizers, the planning of planting types, weeding, defense against insects, irrigation (which had to be correct and timely), and so on.

These foundations that were the basis of labor-intensive agricultural techniques, mentioned in the literature prior to the Qin, became more sophisticated in the Han period.

In fact, in the bibliography of the History of the Han dynasty, under the heading “agriculture” nine titles are listed.

Of these works, only the Book of Fan Shengzhi (Fan Shengzhi shu) still exists – albeit in fragments cited by other agrarian texts.

Another work of great importance is the one entitled “Monthly ordinances for the four classes of people (Simin yueling)” by Cui Shi (? -170 AD approx.), A “farmer gentleman” who compiled this almanac as “manual “For the management of large agricultural estates.

The most interesting thing is that both Fan Shengzhi and Cui Shi had served as public officials, and that they almost certainly contributed directly to promoting the agricultural development of their respective jurisdictions, a fairly common behavior and role among Han administrators.

Parallel to the evolution of agricultural techniques, an evident and remarkable evolution had begun in the realization and use of agricultural tools.

The growers had a real assortment of tools made both in wrought iron and cast iron. We recall that during the Han dynasty, the extraction and processing of iron were a monopoly of the State, which was directly concerned with designing, producing and distributing a rich range of agricultural instruments.

The archaeological discoveries indicate to us without equivocation that the equipment during the Han dynasty, thanks to a high-tech metallurgy, was perfect forge; iron was tempered, beaten in its pure state, hardened in carbon (therefore transformed into steel).

All this made it possible to produce numerous machine tools as well as iron tools, such as spades, hoes, excavators, plows, sickles, and sickles, all differentiated into subtypes based on their particular functions.

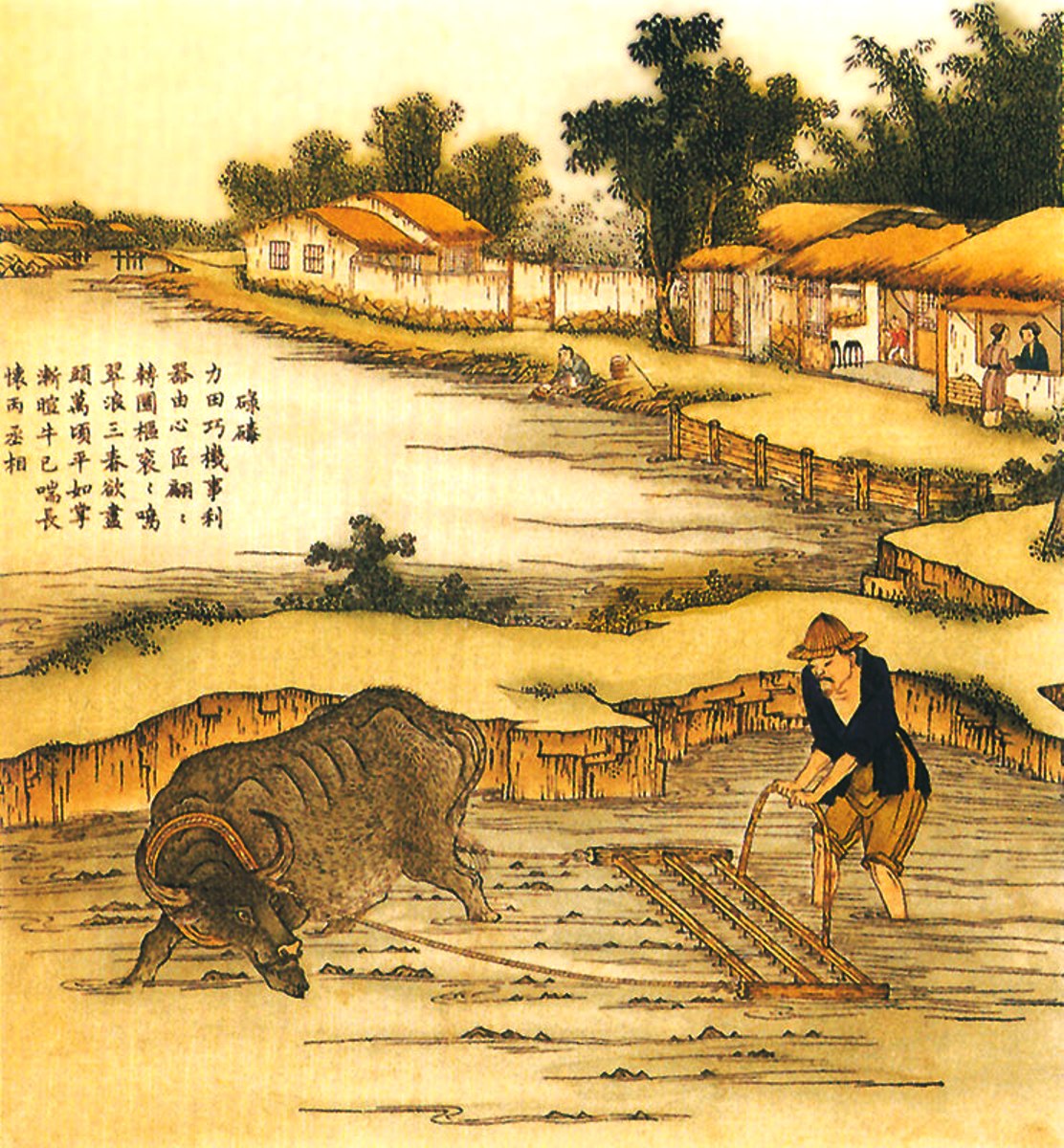

This specialization is more evident if we examine the evolution to which the plow was subjected. The plow, during the Han period, consisted of a ploughshare provided with a blade and a rear porch slat; this was pulled by an ox or a pair of oxen or horses and was able to open the ground in depth, overturning it so as to create the sluts.

The different size and forge of the plows suggests that depending on the type of processing, deeper or reclamation, heavier plows were used, while lighter plows or tools were used to break up lumpy earth plates.

Interesting was the care for the preparation of the sowing witnessed by the realization of seeders that were made by some tubes fixed to a small ploughshare, through which the farmer threw the seeds in the worked soil being able to regulate the distance between the plants. To increase fertility but above all the reclamation of new lands the Han government encouraged the use of the plow and, in particular, urged the populations that lived in the border regions to use the plow pulled by the ox. The archaeological evidence that has been collected confirms what is documented by the texts, namely that in areas very distant from each other plows of similar structure were used.

Guido Bissanti