Ecodemocracy

Ecodemocracy

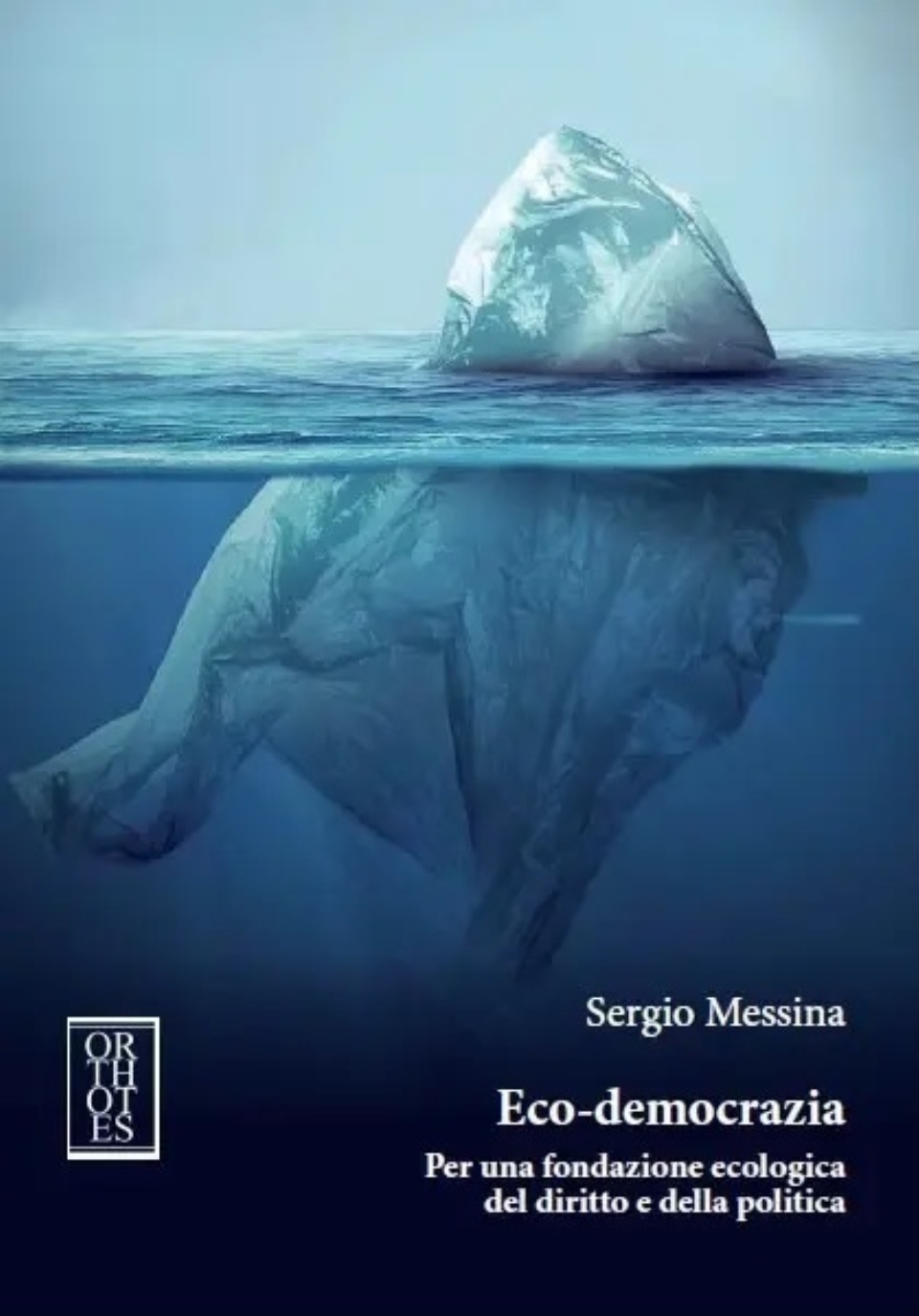

The shipwreck of the species. Looking for a radical regeneration. Review of Sergio Messina’s book “Ecodemocrazia. For an ecological foundation of law and politics”, Orthotes publishing, Nocera Inferiore (SA)

The author, Sergio Messina, with his monograph Eco-democracy. For an ecological foundation of law and politics (2019)1 , of high scientific depth and full of food for thought, he went so far as to want to consider Nature in a certain way as an entity endowed with a moral and political “dignity” equal to that of human beings.

This reflection highlights the awareness, which has emerged in recent decades, of the manipulative effects that technology has on life with the likelihood that this could endanger the survival of humanity itself and the possibility of building alternative visions of civil coexistence with respect to economic homologation, social and cultural produced by neoliberalism.

Starting from the methodological assumption that belongs to the ecological sciences, on the basis of which Nature can exist without the Human but not the Human without Nature, the text opens with a historical-philosophical excursus that involves a basic interdisciplinarity, aimed to highlight how for a long time our species has perceived itself as an independent and separate entity from the context in which it is immersed, not imagining, however, that it is precisely the second pole of the relationship that constitutes the cement of existence and its development evolutionary.

Over the last 50,000 years, Homo sapiens has in fact diversified not only on the somatic, linguistic and cultural level, but also from the point of view of the forms of adaptation to the natural environment; for much of this period the subsistence of humanity depended on what natural resources offered in their spontaneity. Only later, that is, in the modern era, did a “dominant” epistemology emerge, justified by the mechanism and reductionism of Western science, exacerbated even more by the technological and economic development of the industrial revolution and at present by the financialization of ‘economy.

For this reason it should be noted that today, according to various scientists, we have passed through the Anthropocene2 era in which the Earth undergoes such large-scale changes as to cause real ecological upheavals depending precisely on anthropic impacts such as climate change, the loss of biodiversity , and the pollution of environmental matrices (air, water, soil). This is the framework in which the book moves and which directs us towards many questions rather than proposing pre-packaged solutions.

One of the main questions Messina poses is: what could be the compass for our actions, both personal and socio-political? We must start – the author argues – first of all from an urgent question of method: the limited resources and the greater ecological footprint3 that especially the more “developed” countries produce both in terms of entropy and social and economic injustice.

The role that the law assumes and in particular the precautionary principle in prescribing prudent behavior, but at the same time proactive in relation to the speed with which negative effects can be produced by human beings (extraction, manipulation, waste, absorption, etc.) compared to the length of the regeneration times of natural resources. This has determined (the author underlines starting from the orientation of complex thought4 ) an unpredictability of the consequences of the same technical-scientific and economic development with regard to both the entire planet and the more fragile human beings who inhabit it.

In realizing how the philosophy that inspires precaution is based on the awareness of this vulnerability which pertains on the one hand to the asymmetry between human beings and the system-nature, on the other to both personal and political commitment, Ecodemocracy even before that a philosophical-political text is characterized as a philosophical essay on the more careful knowledge we can have about the world around us through the interconnection between knowledge, but also through the unveiling of the powers that accompany them.

And it is in fact here that Messina follows and at the same time criticizes post-modern trends, rediscovering the theory of communicative action by Jurgen Habermas5 but reinterpreted through the lens of Anglo-Saxon political theorists such as Robyn Eckersley, John Dryzek and John Barry, whose contributions have brought out new “green” political categories that reflect the link that exists between ecology and society.

It is no coincidence that the central examination of the book concerns the political effects that are produced by the aforementioned nexus: how the action of a large part of the pantheon of political and economic subjects in the “pluriverse”6 of the socio-natural systems acts and “feedback” global governance?

If we think only of how the neoliberal system in supporting a continuous increase in production, capital, consumption and profit still inspires environmental policies today, we realize how the “ecological deficit” of the Earth’s physical resources (energy and raw materials) does not actually constitute an order of priority on the global agenda except to the extent that this occurs by balancing it with the untouchable principle of “maximizing” individual utility.

On the contrary, Messina warns, by adhering to a “deeper” vision of philosophical-political environmentalism, a truly sustainable development teaches us to live precisely within the limits of one and only Planet; ignoring the ecological footprint in fact involves two great risks: one at an ecological level, the other at a socio-economic level, although the two levels are closely intertwined.

On the ecological side, an irreversible alteration of biogeochemical cycles and a gradual depletion of resources to fund any reserves; on the socio-economic side, the high probability of increasing the already current and stratified inequalities, especially towards those who suffer the environmental and climate crisis in a more pressing and invasive way.

In the face of such a scenario, the outcome of this juridical and political reflection of the author also appears: at present some companies feel the need, as well as the inevitability of techno-scientific progress, while others see the opposite in the development based on growth a potential threat to both human dignity and the natural environment.

So how to find concrete solutions in order to reconcile the “rights of the person”7 with the survival of the species, by safeguarding the planet that it inhabits? In other words, how should politics act?

The author outlines some viable paths which, however, call into question the traditional categories of philosophical and legal-political thought, in particular whether democracy is suitable for facing the climate and ecological challenge in general. Without a paradigm shift involving both thinking and policy, the interplay between climate change, biodiversity loss, food security and natural resource consumption will accelerate towards biosphere collapse, the likelihood of which in turn threatens livelihoods above all of the populations most vulnerable to global warming, which would suffer, as is known, more intensely from the impact of natural disasters, largely triggered by a destructive and profoundly unfair economic system.

Citizen consultation and good multilevel governance, in this scenario, are a necessary but not sufficient condition for governments that are attentive, transparent and responsible. In fact, still in the opinion of the author of Ecodemocrazia, a greater involvement of civil society in what concerns public decisions would be needed, rethinking the institutions of participation in a perspective of co-administration and co-decision for nature, if not with nature8 .

A model, indicated and described in the text, which has seen the social and environmental crisis faced in accordance with the perspective illustrated above is that of various indigenous populations coming mainly from the southern hemisphere.

First fought, defeated and marginalized in their own lands, they later saw their “non-anthropocentric” conceptions on the relationship between humanity and nature integrated into some very innovative Constitutions in terms of both legal dogmatics and principles, due to their role critique of Western lifestyle and well-being9 .

These Constitutions have become an essential point of reference for a turning point that environmental law is taking in a more “ecological” direction, but which would require a better integration between indigenous “knowledge” and “Western science” in accordance with a radical change of vision and mentality and not just of technology.

The book follows these aspects, following a historical-evolutionary and philosophical-political line as evidence of the deep bond with the earth and with the natural environment that characterizes these cultures, different from the marked utilitarianism of Western societies. But precisely for this reason it can actually be argued both in the opinion of Messina and of the writer that we are in a certain sense united with the former thanks to a call addressed to the “globalized” peoples who instead have largely lost this bond.

This reference constitutes the constant trace and at the same time the battle cry of the book, which in the noble aim of reconciling consensus and conflict sees in the crisis of modern democracy an opportunity not only of defense against technocratic degeneration, but also a source for a transformation thanks to which it is still possible to imagine and implement horizons of common sense.

Caterina Corsica

Sergio Messina (author of Ecodemocrazia) is a technologist-lawyer at the Directorate of Legal Affairs, Prevention of Corruption and Transparency of the ENEA registered office. Graduated in Law at the Federico II University of Naples with a Masters in Environmental Law at the University of Siena; admitted to the legal profession at the Order of Lawyers of S. Maria Capua Vetere (CE). He is PhD in Philosophy of Law and past visiting researcher at the Strathclyde Center of Environmental Law and Governance in Glasgow. He is an expert in numerous Pon projects in the field of ecology and law at first and second grade secondary schools. He has published numerous articles in the field of ethics and environmental law including the monograph “Eco Democracy. For an ecological foundation of law and politics”, Orthotes, Nocera Inferiore 2019, “Global” constitutionalism to the test of climate change . For a possible metamorphosis of international environmental law, in “Theory of social regulation” (2020) From urban park to public ‘agorà’: a multifunctional project for a ‘glocal’ civic identity, in “Scienze del Territorio”, no. 8 of 2020 Conversation with Giorgio Nebbia in G. Nebbia, The ecological dispute. History, chronicles and narratives, The school of Pythagoras, Naples 2015.

Caterina Corsica has a degree in Economics and Commerce with a specialization in Sciences and Techniques of Public Administration at the Second University of Naples (SUN). You defended a master thesis, cum Laude, in Comparative Administration Law entitled “Environmental principles in the Charte de l’Environnement. The Problems of Precaution”. She is a trainee associate at the Union of Young Chartered Accountants and Accounting Experts of North Naples (CE). Past visiting researcher at UNIDROIT (Rome). Among her publications, she has published, in “The Bits in the Age of Globalization”, in International and Comparative Law Review, 2018, vol.18, n. 2

(https://content.sciendo.com/view/journals/iclr/18/2/article-p7.xml), also on the duty of states to guarantee sustainable development; in “The incentives of the Green New Deal: submission of applications starting on 17 November 2022” in Norms & News. Newsletter n.11/2022, p. 3, UGDCEC Napoli Nord, https://ugdcecnapolinord.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/UGDCEC-Napoli-Nord-Newsletter-n.11_2022.pdf addresses how Italy, among the various measures, is appropriate to the European “Green New Deal”, its current research topic, which aims to make Europe climate neutral by 2050.

1 S. Messina, Ecodemocrazia. Per una fondazione ecologica del diritto e della politica. Monografia pubblicato da Orthotes editore, Nocera Inferiore (SA), 2019. 2 Cfr. J. Mc Neill Environmental Humanities, VideoDictionary 2014 (disponibile online). 3 Tale indicatore esprime in termini numerici la superficie planetaria necessaria alla produzione delle risorse e all’assorbimento dell’anidride carbonica immessa nell’atmosfera e dai rifiuti prodotti dalle attività antropiche. Cfr. Rees W., L’impronta ecologica, Ambiente, Milano 2000. 4 Cfr. E. Morin, Introduzione al pensiero complesso. Gli strumenti per affrontare la sfida della complessità, tr. it. di M. Corbani, Sperling & Kupfer, Milano 1993. 5 Cfr. J. Habermas, Teoria dell’agire comunicativo, Il Mulino, Bologna 1986 (1981). 6 Cfr. A. Kothari, A. Salleh, A. Escobar, F. De Maria, A. Acosta (a cura di), Pluriverso. Dizionario del post-sviluppo, Orthotes Editrice, Nocera Inferiore (SA) 2021. Libro recensito dallo stesso Sergio Messina inhttps://www.ilmanifestoinrete.it/2021/12/05/pluriverso/. 7 Cfr. G. Limone, Dal giusnaturalismo al giuspersonalismo. Alla frontiera geoculturale della persona come bene comune. Graf, Napoli 2005. 8 Cfr. M. Carducci, Eco-democrazia. Per una fondazione ecologica del diritto e della politica. Monografia pubblicato da Orthotes editore, Nocera Inferiore (SA), 2019. 9 Un ruolo riconosciuto da ultimo anche da Papa Francesco (cfr. Jorge Mario Bergoglio, Laudato sì. Lettera enciclica sulla cura della casa comune, Paoline editoriale libri, Roma 2015.