How to fight the carpocapsa in a biological way

How to fight the carpocapsa in a biological way

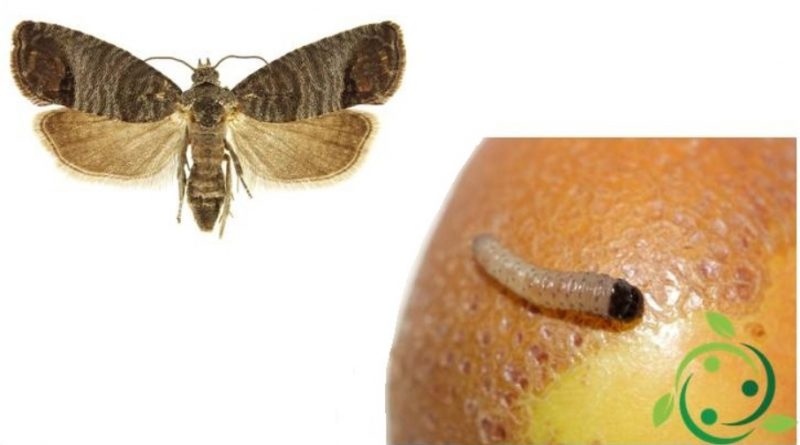

The carpocapsa of the apple tree (Cydia pomonella (Linnaeus, 1758)) is a Tortricide lepidopter among the most harmful in the cultivations of the Pomaceous and other crops as well as the walnut. At the adult stage, the carpocapsa is a 15-22 mm butterfly with wingspan with gray-striated wings in the part closest to the head and with more intense transverse bronzing veins in the back. In this contribution we see what measures to take to contain it and how to fight the carpocapsa in a biological way. In order to operate this we must start from the biological cycle and the damage it causes to tree crops. The larvae, on the other hand, are whitish with a dark head and, over time, however, the rest of the body becomes dark, and then it changes again and becomes yellowish and finally rosy. Their final length is about 15-20 mm. Damage to fruits is determined by larval stages that penetrate into the fruit by digging tunnels into the pulp and becoming easy to identify even outside. Once the development is over, the larva leaves the fruit digging a further exit tunnel. In temperate Mediterranean climates the carpocapsa winters like larva mature in diapause inside cocoons in the recesses of tree trunks or in the ground.

When spring arrives, the larvae cry and, between April and May, the adults flicker, with a maximum in the second half of May. The butterflies are active at sunset and with temperatures above 15 ° C there are couplings from which after a few days follow the ovipositions. The first deposition is isolated on leaves or twigs near the fruit. After a few days the larvae penetrate into the fruits where they complete their development in 20-30 days and, when they reach maturity, they escape to incriminate themselves under the bark of the trees. From the end of the second generation up to August, the second generation butterflies ovate directly on the already developed fruits, so the second generation larvae have a very short incubation time and are active from July to the whole of August. At this point (also depending on the climate) the larvae have two development options: either to enter the diapause, to end the annual cycle or to retest to give rise to the third generation, whose adults flicker from August to September and are active until October. At this point between the first cold and the photoperiod change the larvae repair themselves in the cocoon to spend the winter. The damages, which are more serious and faster in the last generations, cause rotting, fruit fall and sometimes total loss of the product.

To implement the biological defense we must start from the monitoring of insects through traps with specific pheromones, placed in number of 2-3 per hectare, on the branches of the trees. Through these traps, the threshold for the next intervention can be established. When the capture of 2 specimens (males) is exceeded in a week, it is time to intervene through various methods. White oils (better if natural) can be used against carpocapsa eggs. However, if the carpocapsa is still at the stage of a young larva, it is necessary to act with an effective microbiological fight using beauveria bassiana, easily found in suitable formulations. Another possibility is the use of the so-called granulosis virus Cydia pomonella G.V. which only affects the larvae of carpocapsa and must be used promptly, at the time of hatching, following the instructions contained in the formulations. The treatment must be repeated after 8 days. In the control of this insect, however, the alternate use of the various methods is recommended. Moreover against third generation larvae, entomopathogenic nematodes can be used, such as Steinernema feltiae in the autumn period, with external temperatures that must be greater than or equal to 10 ° C. Other systems can be of mechanical type such as that of the band traps in corrugated paraffin cardboard that mechanically capture the larvae that descend along the bark remaining trapped and subsequently burning these bands. There are also anti-insect nets but complex management for intensive orchards.

The last consideration is instead that which follows the principles of agroecology and which today in modern agriculture is often disregarded. The possibility of planting orchards with alternating species, rows, grassing, hedges and plants that biodiversify the orchard are demonstrating worldwide a different way of containing any kind of parasites, since its proliferation is almost always due to an exasperation (specialization) of the ‘agroecosystem to which the parasites respond as feedbacks to restore ecological conditions of lower impact.